There is some evidence to suggest that women with ovarian cancer might be willing to accept lower progression free survival for enhanced health-related quality of life. A study published the December 2014 edition of Cancer suggested that women with recurrent ovarian cancer were prepared to trade several months of PFS for reduced debilitating side effects of chemotherapy, which include nausea and vomiting. The most common adverse reactions to niraparib, which affect about 10% of patients, include thrombocytopenia, anaemia, neutropenia, leukopenia, palpitations, nausea, constipation, vomiting, abdominal pain, mucositis/stomatitis, diarrhoea, dyspepsia, dry mouth, fatigue, decreased appetite, urinary tract infection, AST/ALT elevation, myalgia, back pain, arthralgia, headache, dizziness, dysgeusia, insomnia, anxiety, nasopharyngitis, dyspnoea, cough, rash, and hypertension.

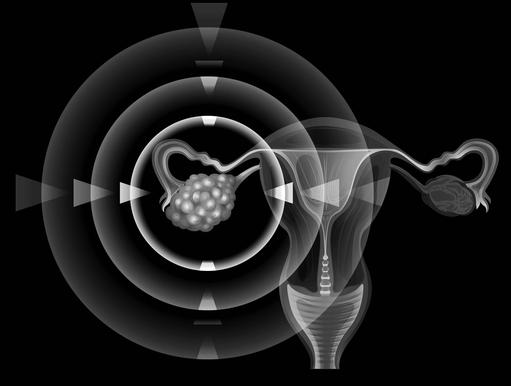

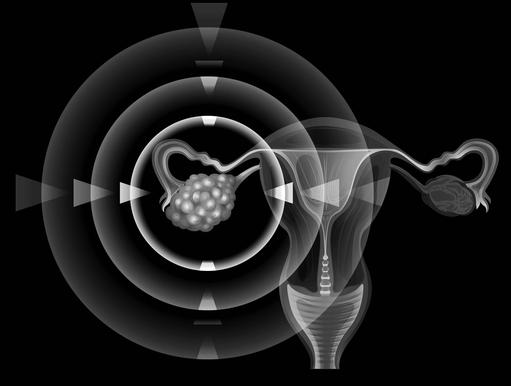

Ovarian Cancer

Epithelial ovarian cancer accounts for 90% of all ovarian tumours. It typically presents in post-menopausal women and is a significant challenge for gynaecological oncologists since most patients are diagnosed when the disease is already advanced and therefore have a poor chance of survival. The natural history of the disease is characterized by a high response rate to primary treatment of debulking surgery followed by platinum-taxane chemotherapy, which is quickly followed by early recurrence and a second-line treatment with platinum; then most patients experience further platinum-resistance and die from the disease. Although ovarian cancer is relatively rare - based on 2013-2015 data 1.3% of women are expected to contract the disease sometime in their lifetime - it is the 7th most common cancer in women worldwide. In 2012 there were 239,000 new cases of the disease diagnosed globally. In the UK ovarian cancer is the 5th most common cancer in females, the 2nd most common malignant gynaecological disease and the 1st cause of death from gynaecological malignancy. The UK has one of the highest incidence rates of the disease in Europe, affecting some 7,500 women every year, and its survival rates are among the lowest. Every year 4,100 women in Britain lose their lives to the disease, which equates to about 11 women every day. Over the past 2 decades there has been a slowing of the rate of diagnosis of ovarian cancer in the UK, which is partly due to the large number of women having taken the oral contraceptive pill after it was made available on the NHS in December 1961 and is known to have a protective effect. According to the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition, over the next 2 decades the incidence rates of ovarian cancer worldwide is expected to rise by 55% and by 15% in the UK. This is mainly because: (i) post-menopausal women are living longer, (ii) populations are increasing, and (iii) there is a significant increase in the rate of urbanization.

The standard of care for ovarian cancer

Although advances in research and technology have contributed additional and sometimes more effective therapy options for women with ovarian cancer such as niraparib and other PARP inhibitors, both the American and European guidelines recommend surgery as the initial approach to ovarian malignancies. After surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy is mandatory in cases of suboptimal debulking, advanced stages, or early stages with a high risk of recurrence. Mike Birrer, Professor of Medicine at Harvard University Medical School, Director of Medical Gynecologic Oncology and also Director of the Gynecologic Oncology Research Program at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center describes the standard treatment for ovarian cancer. “Ovarian cancer is diagnosed surgically. It’s important that the patient undergoes proper diagnostic and staging procedures. This would include an exploratory laparotomy (a surgical procedure, which involves an incision through the abdominal wall to gain access into the abdominal cavity), which would then evolve onto a staging laparotomy, (to determine the extent and stage of a cancer), which would include a TAH (total abdominal hysterectomy), BSO (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, which is when either the uterus plus one ovary and fallopian tube are removed, or the uterus plus both ovaries and fallopian tubes are removed), removal of the ovaries and the uterus. The removal of the omentum (a layer of fatty tissue that covers the abdominal contents like an apron; the procedure to remove it is called an omentectomy, which involves removing the uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes and ovaries), and lymph nodes in the regiterial cavity, scraping of the upper abdomen and then a peritoneal lavage (a procedure to determine if there is free floating fluid, most often blood, in the abdominal cavity). This would give accurate staging for the patient and anything less would be considered less than the standard of care. Once the stage is established and the patient has an advanced stage of the disease, which has spread throughout the abdomen or outside the abdomen, the patient would then undergo further therapy. This would inevitably involve a combination of chemotherapy. The specific regimen would depend, in part, upon the surgical results.” See video below.

Current options for ovarian cancer maintenance therapy

In addition to niraparib, current options for ovarian cancer maintenance therapy include bevacizumab and olaparib. The former is a monoclonal antibody designed to block a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Some cancer cells make this protein and blocking it may prevent the growth of blood vessels that feed tumours, which can stop the tumour from growing. Notwithstanding, bevacizumab can only be given once and improves progression-free survival by just a few months. Olaparib is a PARP inhibitor, which blocks how PARP proteins work in cancer cells that have a BRCA gene mutation. Without PARP proteins, these cancer cells become too damaged to survive and die. In the first instance, olaparib was only approved in patients with a germline BRCA mutation, which accounts for about 10–15% of ovarian cancer patients. In 2014, when olaparib was approved in Europe and the USA, it was the first cancer treatment targeted against an inherited genetic fault to be licensed. Subsequently, evidence suggested that the drug could also benefit patients whose tumours have defects that are not inherited.

Non-specific signs and symptoms

The unresolved challenge for ovarian cancer is that in its early stage it rarely presents with any symptoms. Compounding this is the further problem that later stages of the disease may present few and nonspecific symptoms, which are commonly associated with benign conditions. Were ovarian cancer detected in its early stage when the disease is confined to the ovary it is more likely to be treated successfully. Ovarian cancer suffers from another challenge because screening for the disease in not an option, as we explain below. Further, often women do not know what symptoms to look out for and primary care doctors misdiagnose the disease especially in younger women. This results in about 80% of ovarian cancer cases being diagnosed late when 60% have already metastasised, which reduces the 5-year survival rate from 90% in the earliest stage to 30%. Signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer include abdominal bloating or swelling, quickly feeling full when eating, weight loss, discomfort in the pelvis area, changes in bowel habits such as constipation, and a frequent need to urinate.

A patient’s view “The 3 primary symptoms of ovarian cancer are bloating, feeling full and pelvic pain. Secondary symptoms include fatigue, bowel and urinary issues. In reality women don’t have all the primary symptoms and they may not have any of the secondary symptoms but may have a combination of the 2. The most prevalent symptom is bloating, especially if it persists. If this occurs women should immediately go to their doctors and ask for a CA-125 blood test. And whatever the outcome of the test they should also insist on a TVUS scan. There is no one easy method of diagnosing ovarian cancer and doctors sometime mistake the symptoms for something less serious like irritable bowel syndrome,” says an ovarian cancer patient. In addition to a pelvic examination, the 2 most frequent diagnostic tests for ovarian cancer are transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), which puts an ultrasound wand into the vagina to examine the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries and the CA-125 blood test, which measures the amount of the protein CA-125 (cancer antigen 125) in your blood.

Late diagnosis

According to Christina Fotopoulou, Professor of Surgery at Imperial College London and Consultant Gynaecological Oncologist at Queen Charlotte’s Hospital NHS Trust , “Ovarian cancer is a very silent disease. It has a tumour dissemination pattern of very small nodules spread throughout the whole skin of the abdomen. In the beginning these nodules are so small that they go undetected. The nodules are only detected when they get larger and produce water. So, women with ovarian cancer get abdominal distention and water in their tummies, which prompts them to seek advice from their doctors. But then it’s too late because it’s already at a late stage of the disease.” See video below.

The ‘bar’ is too high to screen for ovarian cancer

Hani Gabra, Professor of Medical Oncology at Imperial College London and Chief Physician Scientist and Head of the Oncology Discovery Unit at AstraZeneca, UK supports Fotopoulou and says, “Ovarian cancer is often diagnosed late because in many cases the disease disseminates into the peritoneal cavity almost simultaneously with the primary declaring itself. Unlike other cancers the notion that ovarian cancer goes from stages 1 to 3 is possibly a myth. In reality these cancer cells often commence in the fallopian tube with a very small primary tumour and disseminate directly into the peritoneal cavity. In other words, they go from the earliest stage 1 directly to stage 3, which renders screening a significant challenge. This is compounded by the fact that ovarian cancer is relatively rare in the population. So, to be effective a screening test would have to be extremely sensitive and extremely specific, which it does not have to be for commoner cancers. The combination of these makes screening for ovarian cancer extremely difficult to achieve.”

Takeaways

Ovarian cancer is a devastating disease, which is diagnosed more infrequently and often at a later stage. Patients are typically older, symptoms are non-specific and easily confused with a number of benign conditions. In its earliest and most curable stage, there may not be any physical symptoms, pain or discomfort. Standard treatment is radical and a harrowing experience for women diagnosed with the disease. About 85% of patients experience a recurrence of the disease after their first treatment cycle, which means that they often face repeated bouts of chemotherapy to keep the disease under control. In a significant proportion of cases even after a second round of chemotherapy the cancer can recur. Previously, at this point patients have had limited pharmacological help, but as research advances, this is beginning to change, and some novel and efficacious drugs are entering the market. Niraparib is one of the latest PARP inhibitors, which has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer.

|

|