Directory

Directory:

Tags:

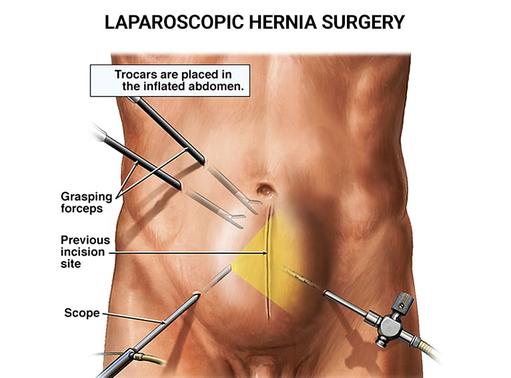

Even though you may have become accustomed to dealing with the discomfort associated with a hernia, that’s no reason to suffer. You can get help by searching for experienced hernia surgeons near me. Additionally, if left untreated, you may develop serious complications that could cause an emergency medical situation. Instead, take the safe, effective route. When you look for the best hernia surgeons near me, call on the doctors at Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics of NJ, PA. They offer a minimally invasive, low-risk procedure called laparoscopic hernia surgery that can end your suffering for good. Don’t postpone relief; call today for an appointment.

Hernia surgery done laparoscopically is a minimally invasive technique for hernia repair. A hernia occurs when an organ or other structure herniates, which means it pushes through muscle or tissue that is supposed to support it, producing a bulge. Most hernias happen in the abdominal area, where they may be mildly irritating or extremely painful.

Hernias can happen to people of any age to both men and women. They can develop gradually or appear suddenly. When you need expert hernia repair surgery, the doctors at Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics of NJ, PA (ASBNJ) are among the best hernia surgeons. They serve patients in northern New Jersey, southern New York and eastern Pennsylvania.

Read more: https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/general-surgery-new-jersey/hernia-surgery/

Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics

81 Veronica Avenue, Suite 205,

Somerset, NJ 08873

Office Tel # (732) 640–5316

Fax 800–689–2361

Web Address: https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/

https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/contact/somerset-nj-office/

Our location on the map: https://goo.gl/maps/Z4oK7ZV4xGXSm6VHA

https://plus.codes/87G7FGF4+WP

Nearby Locations:

Somerset | Hillsborough | Franklin Park | North Brunswick | New Brunswick | Piscataway

08873 | 08844 | 08823 | 08902 | 08901| 08854

Working Hours :

Monday: 9AM–5PM

Tuesday: 10AM–5PM

Wednesday: Closed

Thursday: 9AM–6PM

Friday: 9AM–4PM

Saturday: Closed

Sunday: Closed

Payment: cash, check, credit cards.

Directory:

Tags:

Obesity leads to a host of physical and psychological complications. In addition to low self-esteem, you could be in danger of developing or worsening high blood pressure, digestive issues, back pain, and joint problems. You don’t have to suffer due to the failure of past dieting techniques. The weight loss experts at Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics of NJ, PA are here to help with safe, effective surgical and non-surgical treatments. Although gastric banding is no longer a main stay in our bariatric repertoire, it still has value in certain situations. It’s a minimally invasive procedure that allows you to restrict your caloric intake while developing a healthier lifestyle with the help of your professional weight loss team. Call today to find out if it’s a good solution for you.

What is Gastric Banding?

Placement of a laparoscopic adjustable gastric band is one of the safe and effective. It was first performed in 1978. The initial procedures used a non-adjustable band around the top part of the stomach to divide it into two pouches. Unfortunately, the pouches gradually dilated, and the operation proved ineffective for long-term weight loss.

By 1986, scientists had developed an adjustable band lined with an inflatable balloon, which proved much more effective at reducing weight for patients. If you’re considering having an adjustable gastric lap band placed, the surgical practice at Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics of NJ, PA (ASBNJ) enjoys a world-class reputation. Their commitment to quality patient care is second to none, and they have six convenient locations in central New Jersey to serve you.

Our practice uses the LAP-BAND ™ gastric banding system. We implant two devices in the abdomen: a silicone band and an injection port. The silicone band is placed around the upper part of the stomach, creating two connected chambers of the stomach. The injection port is attached to the abdominal wall underneath the skin and connected to the lap-band with soft, thin tubing. The lap-band is adjustable and several adjustments will be made periodically after the procedure is completed to assure the appropriate level of restriction. The physician uses a needle to inject saline solution into your band through the port, increasing the amount of restriction provided by the band, which in turn can help you feel fuller.

Read more: https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/bariatric-surgery/gastric-banding-surgery-new-jersey/

Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics

81 Veronica Avenue, Suite 205,

Somerset, NJ 08873

Office Tel # (732) 640–5316

Fax 800–689–2361

Web Address:

https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/

https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/contact/somerset-nj-office/

Our location on the map: https://goo.gl/maps/Z4oK7ZV4xGXSm6VHA

https://plus.codes/87G7FGF4+WP

Nearby Locations:

Somerset | Hillsborough | Franklin Park | North Brunswick | New Brunswick | Piscataway

08873 | 08844 | 08823 | 08902 | 08901| 08854

Working Hours :

Monday: 9AM–5PM

Tuesday: 10AM–5PM

Wednesday: Closed

Thursday: 9AM–6PM

Friday: 9AM–4PM

Saturday: Closed

Sunday: Closed

Payment: cash, check, credit cards.

Directory:

Tags:

Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics of NJ, PA (ASBNJ) is a multi-location medical practice specializing in surgical and non-surgical bariatric medicine, hernia repair and acid reflux solutions. From their New Jersey offices, these bariatric specialists serve patients in southern New York, northern New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania for:

Weight loss

Bariatric issues

Hernias

Esophageal diseases

Acid reflux problems

Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics

81 Veronica Avenue, Suite 205,

Somerset, NJ 08873

Office Tel # (732) 640–5316

Fax 800–689–2361

Web Address:

https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/

https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/contact/somerset-nj-office/

Our location on the map: https://goo.gl/maps/Z4oK7ZV4xGXSm6VHA

https://plus.codes/87G7FGF4+WP

Nearby Locations:

Somerset | Hillsborough | Franklin Park | North Brunswick | New Brunswick | Piscataway

08873 | 08844 | 08823 | 08902 | 08901| 08854

Working Hours :

Monday: 9AM–5PM

Tuesday: 10AM–5PM

Wednesday: Closed

Thursday: 9AM–6PM

Friday: 9AM–4PM

Saturday: Closed

Sunday: Closed

Payment: cash, check, credit cards.

Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics

Dr. Ragui Sadek, MDAdvanced Surgical & Bariatrics of NJ, PA (ASBNJ) is a multi-location medical practice specializing in surgical and non-surgical bariatric medicine, hernia repair and acid reflux solutions. From their New Jersey offices, these bariatric medicine doctors serve patients in southern New York, northern New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania for:

Weight loss

Bariatric issues

Hernias

Esophageal diseases

Acid reflux problems

Staffed by some of the most respected doctors in the region and the entire country, ASBNJ has built a practice with the latest equipment and most up-to-date techniques. The staff welcomes you to the practice as family, giving you the attention you desire while answering all your questions. The celebrated medical staff specialize in:

Weight loss surgery, also known as bariatric surgery

Gastric bypass revision, also called gastrojejunostomy

Laparoscopic surgery, or simply laparoscopy

Best hernia surgeons near me

Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics of NJ, PA was built from the ground up to accommodate bariatric procedures. Established as a state-of-the-art facility, it’s one of the safest bariatric surgery programs in the tri-state region. The staff includes everything you may need during your treatment. ASBNJ maintains five offices in Somerset, NJ. Find the closest bariatric center to you in:

East Brunswick

Edison

Marlboro

Princeton

Somerset, the main office

If you’re trying to lose weight through bariatric surgery, you deserve to be nurtured through the process. Each of the bariatric surgery centers is equipped with cutting-edge technology and staffed with compassionate caring professionals. Every office is staffed with all the trained specialists you may need during your treatment. They all work together to provide award-winning patient care.

Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics of NJ, PA is a premier bariatric center in northern New Jersey. Performing weight loss, esophageal and hernia procedures, the internationally recognized specialists help you reach your health goals in an optimal way. We dedicated to continuing education and refinement of the most cutting edge surgical techniques in the field, punctuated by Dr. Sadek’s experience and development of safety protocols leading to one of the lowest complication rates in the Northeast. This dedication to quality care has changed the lives of thousands of patients throughout the NY/NJ area. This bariatric center, with offices near you, performs teen weight loss procedures — as one of the few places in the country to treat teens for obesity. So call today for the appointment that can change your life.

Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics

81 Veronica Avenue, Suite 205,

Somerset, NJ 08873

Office Tel # (732) 640–5316

Fax 800–689–2361

Web Address:

https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/

https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/contact/somerset-nj-office/

Our location on the map: https://goo.gl/maps/Z4oK7ZV4xGXSm6VHA

https://plus.codes/87G7FGF4+WP

Nearby Locations:

Somerset | Hillsborough | Franklin Park | North Brunswick | New Brunswick | Piscataway

08873 | 08844 | 08823 | 08902 | 08901| 08854

Working Hours :

Monday: 9AM–5PM

Tuesday: 10AM–5PM

Wednesday: Closed

Thursday: 9AM–6PM

Friday: 9AM–4PM

Saturday: Closed

Sunday: Closed

Payment: cash, check, credit cards.

Our social links:

https://www.facebook.com/AdvancedSurgicalAndBariatricsOfNJ/

https://www.linkedin.com/company/advanced-surgical-and-bariatrics

https://www.instagram.com/advanced_surgical_bariatrics

https://www.youtube.com/user/NJSURGICALBARIATRICS

https://www.yelp.com/biz/advanced-surgical-and-bariatrics-somerset

https://bariatricsurgerynewjersey.tumblr.com

https://www.pinterest.com/bariatricsurgerynewjersey

https://www.flickr.com/photos/199152749@N04/

https://www.tiktok.com/@bariatricsurgerynj

Find us at: https://www.vitadox.com/practice/somerset-nj-08873/advanced-surgical-bariatrics/VMCiQnhtfGkhsYo9RHg5ab

View other locations Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics has been mentioned:

https://us.centralindex.com/company/1495754302300160/advanced-surgical-amp-bariatrics/somerset

https://www.cylex.us.com/company/advanced-surgical---bariatrics-25479300.html

https://find-open.com/somerset-somerset-nj/advanced-surgical-bariatrics-4004401

https://www.local.com/business/details/somerset-nj/advanced-surgical-%26-bariatrics-148785491

view this profile

Directory:

Tags:

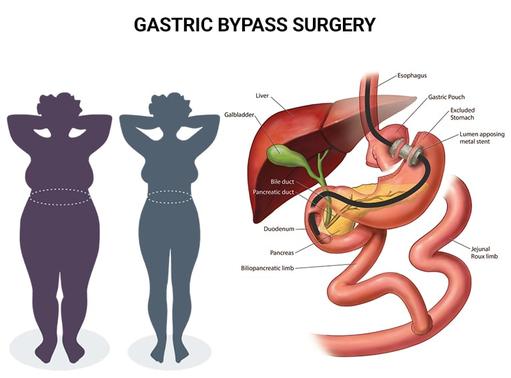

After you’ve tried countless diets, joined a few gyms or visited alternative medicine providers, you’re ready to listen to a licensed doctor about how to lose weight. Turn to the weight loss surgeons at Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics of NJ, PA for advice on how you can successfully reach your weight loss goals. Gastric bypass surgery — considered the gold standard of weight loss treatments — is a safe but effective form of surgery that often results in drastic weight loss. Moreover, you can expect healthier outcomes for any underlying conditions you may have, such as high blood pressure, reduced activity levels, low energy, sleep disorders, back pain and cardiovascular disease. Contact our experts weight loss doctors today to find out how you can take control of your eating and finally lose weight.

When you’re struggling with obesity and haven’t been able to lose weight through diet and exercise, it’s time to consider gastric bypass surgery. Gastric bypass is a common form of bariatric surgery that involves creating a small pouch from your stomach. Then your bariatric surgeon connects this pouch to part of your small intestine. After this procedure, the food you eat passes through the new pouch, bypassing part of your stomach and the first section of your intestines.

The gastric bypass procedure is also called Roux-en-Y because it was developed by Swiss surgeon César Roux, who described it with a stick-figure Y. Although normally an irreversible procedure, gastric bypass surgery can successfully help you lose weight. The Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass creates a smaller stomach. This gastric bypass weight loss occurs because the pouch restricts the amount of food you’re able to eat, so you get that full feeling sooner. The procedure also forces your digestive system to absorb fewer calories from the food.

Read more: https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/bariatric-surgery/gastric-bypass-surgery-new-jersey/

Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics

81 Veronica Avenue, Suite 205,

Somerset, NJ 08873

Office Tel # (732) 640–5316

Fax 800–689–2361

Web Address:

https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/

https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/contact/somerset-nj-office/

Our location on the map: https://goo.gl/maps/Z4oK7ZV4xGXSm6VHA

https://plus.codes/87G7FGF4+WP

Nearby Locations:

Somerset | Hillsborough | Franklin Park | North Brunswick | New Brunswick | Piscataway

08873 | 08844 | 08823 | 08902 | 08901| 08854

Working Hours:

Monday: 9AM–5PM

Tuesday: 10AM–5PM

Wednesday: Closed

Thursday: 9AM–6PM

Friday: 9AM–4PM

Saturday: Closed

Sunday: Closed

Payment: cash, check, credit cards.

Dr. Ragui Sadek, MD

SurgeonDr. Ragui Sadek’s career has been one of significant experience and distinction. Dr. Sadek is a premier surgeon in the New York and New Jersey area. A Clinical Assistant Professor of surgery at RWJ Medical School and the Director of bariatric surgery program at RWJ University Hospital, Dr. Sadek has established a state-of-the-art and one of the safest bariatric surgery programs in the state. His program has a complication rate far below the national average, while providing a cutting edge variety of laparoscopic, robotic, and bariatric surgery techniques.

Dr. Sadek initiated the Bariatric Surgery program at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital where, prior to his arrival, weight loss surgery was not performed. He is now the senior most minimally invasive bariatric surgeon. Dr. Sadek assumed a leadership role as the Director of Bariatric Center of excellence at RWJUH and oversees all of the care rendered to the hospital’s bariatric patients, including anesthesia, radiology, floor and preoperative nursing, and myriad of consulting services.

Dr. Sadek has completed his residency and an advanced laparoscopic and bariatric surgery fellowship at SIUH. Later, he went on to finish a surgical critical care and trauma fellowship at UMDNJ Newark campus. Dr. Sadek joined a private practice in 2006 and performed a wide variety of advanced laparoscopic and bariatric procedures. More than three thousand advanced surgical procedures later, he has established a strong patient satisfaction rate and a solid reputation among the surgical community.

Advanced Surgical & Bariatrics

81 Veronica Avenue, Suite 205,

Somerset, NJ 08873

Office Tel # (732) 640–5316

Fax 800–689–2361

Web Address:

https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/

https://www.bariatricsurgerynewjersey.com/contact/somerset-nj-office/

Our location on the map: https://goo.gl/maps/Z4oK7ZV4xGXSm6VHA

https://plus.codes/87G7FGF4+WP

Nearby Locations:

Somerset | Hillsborough | Franklin Park | North Brunswick | New Brunswick | Piscataway

08873 | 08844 | 08823 | 08902 | 08901| 08854

Working Hours:

Monday: 9AM–5PM

Tuesday: 10AM–5PM

Wednesday: Closed

Thursday: 9AM–6PM

Friday: 9AM–4PM

Saturday: Closed

Sunday: Closed

Payment: cash, check, credit cards.

Find us at: https://www.vitadox.com/doctor/somerset-nj-08873/ragui-sadek-md/F666CbpjZXfKd5Ua6TF4oK

view this profile

Directory:

Tags:

- Each year unhealthy diets are linked to 11m deaths worldwide a global study concludes

- Red and processed meat not only cause disease and premature death from chronic non-communicable diseases (NCD) but also put the planet at unnecessary risk

- Evidence suggests that the health benefits of a Mediterranean diet reduces the risk of NCDs and is better for the Planet

Eat like Greeks, live healthier lives and save our planet

|

|

Directory:

Tags:

|

Directory:

Tags:

|

Directory:

Tags:

|